Including autistic workers

Red in the Spectrum’s Janine Booth spoke about Including Autistic People at Work: removing barriers and challenging discrimination at 1-2-1 Enfield‘s Autism Inclusion conference in June. You can watch a video of the talk here. This is what Janine said:

I’m Janine Booth. I worked for over 25 years as a London Underground station supervisor – apologies for that! [Question from audience: which station?] At lots of different stations; I started and ended at the same station actually – Oxford Circus – but worked at many dozens of others during that time.

I’m now a trainer at Red in the Spectrum, having left London Underground last year. Now I do this kind of stuff [speaking at events]. I’m also a railway content writer because despite having left London Underground, I’m still very nerdy about railways.

I am autistic, also unconfirmed but very obvious ADHD, and, apparently, have specific learning difficulties of a dyslexic type – that’s what the document said anyway.

Including autistic workers: the social model of disability

The first thing I want to do before I talk about work, is to talk about the medical model and the social model of disability. I’m sure some of you have heard of this, some of you might not have heard of it, but it’s fantastic!

What we’re talking about here is different ways of understanding disability within society. There are quite a few different ways, different models for understanding disability within society, but the two main ones, the ones I want to address, are the medical model and the social model.

The medical model is, if you like, the traditional way of thinking about disability, the way we were probably all brought up to think about disability. Essentially, a medical model approach is one that sees the impairment as the cause of disabled people’s disadvantage and therefore concludes that disabled people need to be fixed, treated, or in some way carried as a burden, cared for, cured, pitied, segregated.

Although some of the more offensive manifestations of the medical model have been dropped as a result of a few decades of enlightenment and campaigning, it does still dominate political and legal decision-making.

In the 1970s, there was a new, radical, self-organised disabled people’s movement, and it focused on the demand for the right to live independently, the right to participate in society on an equal basis to everyone else. They soon realised that if they were going to win the argument for that, they would have to challenge the whole way that society views disability.

So, they labelled the way of looking at disability that I’ve just described – the traditional way – as the medical or individual model. And they drew up a new model, which became known as the social model of disability.

This is the essential difference. The social model distinguishes between impairment and disability. It says that impairment is a trait or a shortfall in functioning, but disability is the difficulty caused to people with impairments by barriers that society puts in their way.

I think that for autism and other forms of neurodivergence, we can tweak this model a little bit, because for some people, our autism isn’t even an impairment, it’s a difference – but it’s significant enough a difference that we are still disabled by barriers in society.

You might notice that the social model, as well as being more progressive and more accurate, is actually more practical, because under a medical model approach, if you can’t fix someone then there’s not much you can do for them, but under a social model approach, you identify the barriers and you remove the barriers.

Let’s have a look at how these two models might describe autism and autistic people. A medical model approach might say ‘some people have a disorder called autism which is a disability and causes them various problems’, and that’s probably quite a common view, isn’t it? Saying practically the same thing from a social model point of view, though, you might say ‘autistic people have atypical brain wiring, society does not accommodate this and can distress autistic people: society disables autistic people’.

Both models accept that autistic people are disabled: what they differ on is what disables us. The medical model says we’re disabled by our autism; a social model approach says we’re disabled by barriers that society puts in our way as autistic people, and therefore it is possible to imagine – although it would be quite different from this society – a society in which we wouldn’t be disabled because those barriers would have been removed.

In a workplace context, what’s the difference between a social model and a medical model approach?

Say you’re an autistic worker and you are having a few difficulties at work and you have a meeting with your manager – and I’m going to ask you to use your imagination here, I want you to imagine that the manager wants to be helpful: I know that’s a bit of a stretch, but apparently there are some out there – and so the manager might say to you, ‘Tell me how your autism causes you problems at work’.

We don’t want the manager to ask you that. What we want the manager to say is, ‘Tell me how work causes problems to you as an autistic worker’.

In Red in the Spectrum, I go round the country teaching trade union reps this. If you have this meeting with your union rep is sitting beside you and they’ve been on one of my courses and the manager says ‘Tell me how your autism causes you problems at work’, that union rep will say, ‘Whoa! stop there, wrong question; the right question is ‘Tell me how work causes problems to you as an autistic worker’.’

Some people might think that’s a bit of a semantic difference, but it’s not, it is a massive difference. Under the first version, what you have to do is slag yourself off. You have to say, for example, ‘I hate the fluorescent lights in the office … I’m really sensitive to them …’ or ‘When the 11:00 meeting doesn’t start until 11:45 … I can’t cope with that’. That’s no use, is it? No-one’s going to stop you getting wound up by that because no one’s going to stop you being autistic.

In the second version of the question – ‘Tell me how work causes problems to you as an autistic worker’ – you get to slag the management off! You get to say things like ‘Those fluorescent lights you have in the office cause me distress and I can’t concentrate on my work’ or ‘When you don’t start the 11:00 meeting until 11:45, that winds me up no end’.

In that version, not only are you not slagging yourself off, but you’re much more clearly pointing to solutions for you as an autistic worker, aren’t you? Because then you can say, ‘If we replace the fluorescent lights with dimmable full-spectrum lighting, that would make things better. If we make sure the 11:00 meeting starts at 11:00 that would be really good, or if we really can’t start it till 11:45, schedule it for 11:45’.

What you’re doing is identifying barriers to autistic workers and removing barriers, and you’re talking about what’s wrong with the workplace not what’s wrong with you, the autistic worker.

100, 150, 200 years ago, disability meant something different from what it does now. It meant that you were some sort of category of person who was excluded by the law from certain things. So, it was a gender thing as well: there was a disability associated with being a woman that you couldn’t vote, you couldn’t stand for public office. So, in a way, we’re going back to the original meaning of disability – that it’s something that society does to you.

It’s about where you look for disability: do you look in the person’s head or body, or do you look in the society around them? The social model is about looking at the society around them.

Do autistic workers have to change?

The question I want to pose here is: do autistic workers have to change to fit in at work, or can work change so that we can take part? It won’t surprise you to know that I’m angling for the second one of those.

I’m going to mention my book now. I don’t have any copies to sell you, so don’t worry, I’m not just selling to you! But the reason I wrote a book called ‘Autism Equality in the Workplace’ was that I got hold of a load of books about autism and employment and they were all about how autistic workers could pretend to be neurotypical in order to fit in at work, and one of them in particular said to me: ‘Write something different’.

There was a bit where this autism coach in America was writing about an autistic worker called Adam who she was coaching, and Adam was getting in trouble at work for not making eye contact during meetings, so she trained him to make eye contact during meetings. I’d have rung up the management and told them to stop judging him for not making eye contact in the meetings!

So, I’m going to take an approach that is: don’t change autistic workers, change the workplace, change jobs.

Ten ways in which workplace disable autistic workers

Taking a social model approach, it is the workplace that disables us, so what I’m going to talk about next – because I’m an autistic stereotype and everything has to be in lists of ten – is ten ways in which workplaces disable autistic workers. Not, note, ten ways in which being autistic disables autistic workers, but ten ways in which workplaces disable autistic workers.

Barriers to autistic workers 1: Getting a job in the first place

A lot of us leave school with qualifications that don’t show our true abilities, because we were taught and assessed in ways that don’t suit us. Not only does that mean that we can’t show our abilities with our qualifications, it’s probably had a corrosive effect on our self-esteem and confidence as well.

Then there’s a lack of helping finding the right job. Then there’s jobs being not being advertised – only 15% of jobs are publicly advertised, the rest of them you need to be plugged into some kind of social network to find out about, and we’re probably less likely to be plugged in than other people are.

Then you have job adverts. It wouldn’t surprise you to see an advert that says something like ‘Friendly, outgoing team player required for job as computer programmer’. I don’t see why you need to be a friendly, outgoing team player to be a computer programmer. Why can’t you just sit in the corner programming your computer and then interacting with people when you really have to? Employers are adding irrelevant personal characteristics to job descriptions and adverts. It’s a form of personality gatekeeping – they’re trying to get people who will go for a drink with them on a Friday night after work and chat about the football with them, etc.

That was a hypothetical example. Here’s a real-life example from my last couple of years at London Underground. Through the Equality Forum, on which I represented the RMT trade union along with other people, we took them to task because they were advertising for station assistants – they call them ‘customer service assistants’, but they’re station assistants – and they wrote, ‘Are you helpful and are you approachable?’ – that’s fine – and ‘Do you have an outgoing personality?’ – that’s not fine.

You do not need to have an outgoing personality to tell people how to get from where they are to where they want to go, or to evacuate a train, or to evacuate a station in an emergency. ‘Friendly and and approachable’ is fine because you want to be able to help people, but you don’t need to bound across the ticket hall and offer them fries with that. They just want to know how to get to where they’re going.

Then you get past all that, and you get as far as the interview – and other forms of torture – where you are asked ridiculous questions, and when you give them literal replies because you’re autistic and a literal thinker, they think you’re taking the piss, don’t they? They say something like ‘How did you find your last job?’ and you reply ‘I found it in the newspaper.’ Apparently, that’s not what they meant.

A lot of people have been demanding – and some employers are beginning to agree to this, which is good – that autistic job applicants be sent questions in advance. Yes, but I want to expand on that a bit: it would be much better if everyone were sent the questions in advance. Why should you have to tell a prospective employer that you’re autistic? Sometimes when autistic people have asked for the questions in advance, the employers said, ‘That wouldn’t be fair on everyone else’.

But I didn’t say you shouldn’t send them to everyone else! Send them to everyone, then everyone’s got time to think about them. If you don’t get them in advance, most autistic people will sit there and think about it for three or four minutes and meanwhile the interviewers are thinking, ‘Who’s this weirdo? Why aren’t they answering straightaway [like a neurotypical person would]?’

Interviewers, like most neurotypicals, are weird! They talk funny and they ask you questions that they don’t want an answer to. They ask questions like, ‘What have you got that the other applicants haven’t?’ How do I know?! I haven’t met any of the other applicants. ‘What can you bring to this job?’ I could bring my boots and my lunch box.

Why on Earth are we using exams and interviews to hire people for jobs? Exams only partially test your knowledge of the subject; they mainly test your ability to pass exams. Interviews only partially test your knowledge of the subject; they mainly test your ability to bullshit – I mean perform – in interviews. Unless the job that you’re applying for involves taking exams and being interviewed, they are not very good judges of how well you could do the job.

Barriers to autistic workers 2: Getting on with the job

You get over all those hurdles, and the second lot of barriers to autistic workers is getting on with the job. You’re going to get an induction in a new job; they’re going to tell you all about the technical aspects of the job, but they’re not going to tell you anything about the social aspects, because you’re supposed to pick that up. But autistic workers don’t do that; that’s what neurotypicals do. So, you end up not knowing what you’re supposed to do on your breaks; not knowing what subjects it’s alright to talk about at work and what isn’t all right to talk about at work, etc.

You’re given some form of training, which might or might not suit your learning style. They might just give you a big wordy manual to read through and that might suit your learning style but it might not.

They overlook our strengths. I represented a guy about ten years ago on London Underground, who was applying to be a train driver. He was autistic and he told them right from the start that he wanted to be a train driver. But they sent him to work on a station – not just any station, but Wembley Park, the local station for Wembley Stadium: can you imagine more of a hellhole for an autistic worker? Probably not.

They sent him a practice paper before he sat the driver’s exam, and then when he did the exam, it was laid out differently from the practice paper, so it freaked him out, he didn’t finish it and he failed. I took it up as his union rep, and we spent a long time explaining autism to these managers, explaining the law to these managers, explaining really basic stuff to these managers (who are paid much more than others because, you know, their knowledge is superior, except apparently it wasn’t).

We got him the job in the end, and he’s been a train driver for ten years without having any problems or making any mistakes, and he now teaches other people to drive trains. One thing that struck me after all that process was that I had sat in these meetings with this autistic worker and these managers for hours and hours and hours talking about why his autism isn’t a problem, and they never considered whether it might actually be an asset.

The guy’s autistic special interest since the age of two was London Underground train stock. He knows more about London Underground trains than anyone else I’ve met (and given I worked on London Underground for over 25 years, I know a lot of people who know a lot about London Underground trains!). He’s the sort of person they should have head-hunted for that job, and yet all they ever did was talk about whether it was a problem or not.

When you apply for a promotion, you just have to go through the same obstacles all over again.

Barriers to autistic workers 3: Workplace communication

Autistic. workers may communicate differently from non-autistic people, but workplaces usually assume neurotypical methods of communication, disadvantaging those who communicate better in a different style.

This is where I get to tell you a funny but illustrative story. There was an autistic guy who got a job as a station assistant at Newcastle Central station. Station assistant is an entry-grade, dogsbody kind of job. The supervisor wanted him to sweep platform one, which is the platform from which trains to Carlisle go, so the supervisor said to him, ‘Go and sweep the Carlisle platform’. You worked out what he did, didn’t you?

He went and got his broom, he went to platform one, he waited for the next train, got on it, went all the way to Carlisle, got off, swept the platforms, got back on the next train, came back to Newcastle, reported back to the supervisor about six hours later – ‘Where the feck have you been?!’. He’s only done what he was told to, hasn’t he? Personally, I’d love to have been the station supervisor at Carlisle: I’m sitting there, feet on the desk, thinking ‘Aw, I’m going to have to go sweep the platforms in a minute’, and then the train comes in, bloke gets off, sweeps them for me and leaves. That would be great!

A slightly more vulgar funny story is that on London Underground, the informal term for an informal break is a ‘blow’. On my first day at work at Oxford Circus, the station supervisor said to me, ‘Go over to the exit gateline and give Derek a blow’. That’s not in my job description!

Workplace jargon can be a massive obstacle to autistic workers.

Barriers to autistic workers 4: Social interaction

The fourth area in which autistic workers face barriers is social interaction – mainly that there’s so much of it! It is exhausting sometimes. We can get through the day and then we go home and just collapse, and can’t do anything until the next day.

Teamwork. I can accept that some jobs, for example footballer, require a degree of teamwork (Cristiano Ronaldo’s evidently forgotten that, but there you go). However, I think that a lot of employers fetishise teamwork. They make a really big thing about it and make you part of a team when actually you could work on your own 90% of the time and then just join in every now and again. They’re putting you in team meetings, team away days, team this, team that, team the other, sending you emails that start ‘Team’, which really annoys me!

Fitting in. Why is it when you have a group of people there and they’re not interacting with the one person there, why is this person accused of not fitting in, rather than these people being accused of excluding that person? It’s because when you’re in a minority, you get blamed.

Insistence on eye contact. People still do this thing where they think that if you’re not staring at them then you’re rude or not interested, whereas a lot of us find eye contact uncomfortable, even painful, intrusive, and, I think, illogical – because when you have a conversation with someone, the organs you’re using are your ears and your mouth, so a social protocol that says you have to lock a completely different part of your body with the other person, to me is about as rational as insisting that people hold hands while having a conversation. I told you neurotypicals are weird.

Barriers to autistic workers 5: Sensory issues

Workplace environments are usually geared to typical sensitivities, causing distress to people with intense or unusual sensitivity to bright lights, or darkness, colour, sounds, textures, heat, cold, etc, or whio find it difficult to work in conditions which are overstimulating or cluttered or busy or congested or cramped, as a lot of workplaces are.

Here’s an example of another union member and autistic worker I represented when I was on the Underground. Nick works on a group of stations, two of which have bright, fluorescent lighting in the control room, which makes him distressed. He also finds the synthetic uniform material uncomfortable and the company was taking a long time to provide uniform in cotton. Nick plans his schedule for each day in advance, so when his duties are changed at short notice this is upsetting.

His manager agreed adjustments that he’s not given duties at those two stations and that his duties are not changed at short notice. But he’s repeatedly found himself being allocated duties at the wrong stations and having his duties changed at short notice and having to say, ‘Excuse me, I’ve got these reasonable adjustments.’

That’s one of the reasons – and I’ll probably repeat this point over and over again – why reasonable adjustments for individual autistic workers are good but workplace change is better. Much better would have been to just get rid of those fluorescent lights and put some full-spectrum lighting in, rather than making reasonable adjustments just for him.

Barriers to autistic workers 6: Organising work

The sixth area in which workplaces disable autistic workers is the way that work is organised. Not every workplace is a factory, but most of them think they are! Most of them function like they are, and therefore everyone is expected to work in exactly the same way at exactly the same speed.

It can cause autistic workers problems by distracting us or interrupting us or creating problems with time management or pace of work or perfectionism. The employer probably wants you to make twenty saleable widgets every hour where you want to make five perfect ones.

Barriers to autistic workers 7: The trouble with managers!

I could do a whole separate talk on this, but we’ll just have the one slide. One trouble with managers is that they don’t know much about autistic workers and neurodiversity – that bit isn’t their fault because they haven’t been trained about neurodiversity by their managers.

You do get management favouritism – blue-eyed boy and girl syndrome – and if you’re the workplace weirdo, you are probably less likely to be one of the manager’s favourites.

Disruptive supervision: standing behind you, telling you to do it differently when you’ve worked out a way to do the job that works for you. Bossiness in general.

Performance management and attendance management can be two of the most horrible things about the modern workplace. They are set out so that everyone has the same targets, they’re all tick boxes, they take no account of differences between people.

Here’s an example of some poor management of a London Underground worker. Simon’s an autistic worker, a train driver. Simon received an instruction from service control to take his train out of service at the station he was approaching. Control could have given this instruction earlier but did not. As Simon took the train into the sidings, he passed a signal at danger.

A manager interviewed him, asking why this had happened. He didn’t say how much detail he wanted, so Simon, who was already anxious because he was in trouble, gave a lot of information about himself including that he was autistic, and the manager instantly decided that this was the reason he made a driving error. He ignored all other factors and stood Simon down from driving, which means he wasn’t allowed to drive trains and he had to work in the station for a while.

His union rep – that was me – asked management to arrange a cognitive assessment, which showed that Simon was able to drive trains and identified ways to support him. Now he’s driving trains again. That whole process took nearly two years, which not only was horrible for Simon – not knowing whether he was going to keep his job and having to work on stations when he’d much rather be driving a train – but London Underground, a publicly-owned company, spent public money paying him a train driver’s wage to do a station assistant’s job.

Barriers to autistic workers 8: Bullying, harassment, discrimination

Far too many autistic workers get mocked or belittled, get excluded socially, are seen as eccentric or weird.

This happens particularly with stimming. You might be an autistic worker who, to get through the day, likes to pop out to the car park and skip sideways around it for two minutes every couple of hours. That might help you regulate yourself. Do that and you will soon become known as the workplace weirdo. And yet no-one has yet been able to explain to me how that is different from a neurotypical person needing to pop out and have a fag every couple of hours.

We all have different ways of getting through the working day, don’t we? It’s just that some are acceptable and apparently some aren’t!

Not surprisingly, a lot of autistic workers stay in the closet and don’t know whether to disclose being autistic or not.

Barriers to autistic workers 9: All change!

It’s well known that we don’t like change – whether it’s disruption to the daily schedule, or changes to the way we work, or major reorganisations.

But actually, there’s one type of change that is the worst: imposed change. Your boss turns up and says ‘Right, we’re going to do everything differently now. You’re going to do that differently. Your job title has changed. We’re relocating to another city fifty miles away.’

One of the most important roles of a trade union is to insist that any kind of workplace change is negotiated. Being negotiated, you can then raise the issues. It means it comes in over time; it means you can be engaged with the process.

Barriers to autistic workers 10: Job insecurity in the time of austerity

We are in a time of austerity and have been since 2008. There’s been a massive growth in temporary, casual and zero-hours contracts, which aren’t great for anybody, but if you’re an autistic worker who relies on routine and you don’t find out what you’re doing at work on a particular day until you get a text message at 7 o’clock the previous evening, then that’s just unbearable, it’s intolerable.

There are job cuts, redundancies and unemployment, and even if you’re not the person whose job gets cut, you end up doing the jobs of the people whose jobs do get cut and your workload goes up and pressure increases, and that’s going to have a particularly severe effect on us.

Removing barriers to autistic workers

So, making the workplace more autism-friendly – how do we do that? We identify barriers to autistic workers and then we remove those barriers.

I’m not going to go back through the entire list of ten things suggesting ways of removing the barriers because what I want people to get in the habit of doing is identifying the barriers to autistic workers and coming up with ideas of how to remove them. But here are some examples:

- a personal workstation – better still, ban hot desking completely; but if you do have that nonsense, then at least an autistic person should be able to have a personal workstation and not have to not know what desk they’ll be working on until they turn up at work each day;

- frequent breaks, to get a break from the sensory overload or the social interaction or whatever;

- quiet space – every workplace should have one;

- full-spectrum, dimmable lighting;

- mentoring: it can help an autistic worker to have a mentor at work;

- control over how you work.

Maybe if the autistic worker or an ADHD worker can’t sit still and concentrate through a four-hour-long, boring meeting, maybe the autism and ADHD aren’t the problem; maybe the four-hour-long, boring meeting is the problem.

To repeat a point I made earlier – I’m going to say it again because I think it’s so important: reasonable adjustments for individual autistic workers are good; changing the workplace is better.

People’s go-to thing tends to be ‘What reasonable adjustments can I have?’, and that is important, but I think it’s Plan B. Plan A is an accessible job, because if the job were accessible to start with, it wouldn’t need adjusting. Every time a reasonable adjustment is agreed, it’s an admission of failure, it’s an admission of inaccessibility, because if something needs adjusting, it’s because it wasn’t accessible to you in the first place.

Autistic workers: Know your rights!

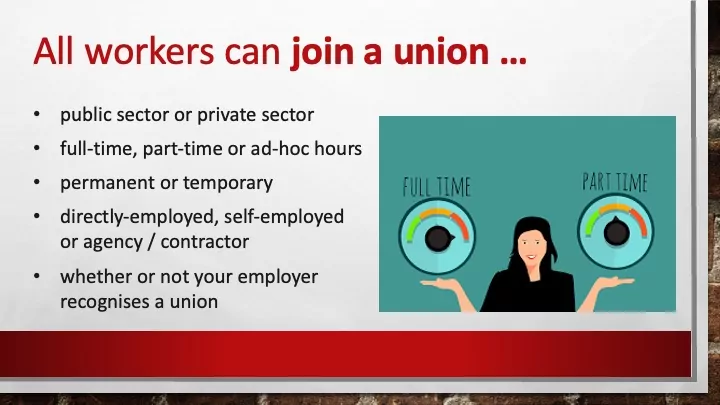

I want to encourage you to know your rights as an autistic worker, including your rights to freedom from discrimination. Discrimination legally comes in lots of different forms: freedom from harassment, reasonable adjustments, the right to complain, to take out a grievance and not be punished for that; and the right to join and be represented by a trade union.

I want to emphasise that point, because if you’re not getting your rights, what are you going to do about it? You can fight it on your own if you want, but fight as part of a union then you are a lot stronger.

I’m not going to say to you ‘Join a union because they’re all perfect’ – they’re not, and actually most them are quite bureaucratic. But a lot of them have made a lot of good progress on disability rights. For example, RMT on London Underground has saved the jobs of at least six autistic workers in the last couple of years, who were about to go down the road until the union rep got involved. A lot of unions are getting much better.

If you want one example of a union I think is quite good on it – believe it or not – is the Fire Brigades Union. The FBU this year for the first time set up a Disabled and Neurodivergent Members’ Forum. That’s in an industry where most people think ‘Disabled people don’t do that, they can’t fight fires’.

Well, they can, and there appears to be a disproportionate number of dyslexic people in the fire service. It might be due to it being a job that doesn’t involve much reading and writing, but also it might be because it’s a job that involves navigating your way around buildings, and dyslexic people are significantly better than average at that.

But lots of unions are really making an effort now – more than 75% of union members are now in a union that has a specific disabled members’ structure in it – like a disabled members’ committee that enables us to bring up our issues.

What can a union do?

It can represent you as an individual autistic worker. That might be if you are trying to get reasonable adjustments; it might be in a grievance; you might be in trouble.

It can campaign for collective workplace change. That might be for change that’s specifically good for autistic workers like getting rid of the fluorescent lights, or it might be something that’s good for everyone including us, like a shorter working week.

Let’s go on a quick tangent about the shorter working week. I was at a parliamentary thing on autism and employment several years ago and there was a discussion about how a lot of autistic workers can’t work full-time, and everyone was accepting this point and everyone on the panel was saying that there must be more opportunities for autistic workers to work part-time.

I said I agree, but I want to go further than that and say let’s rethink what we mean by full-time working week, because working 48 hours a week is not acceptable for anybody. Perhaps if the full-time working week were, say, 32 hours over four days, then a lot more autistic workers would be able to work full-time, or if they work part-time, it would be a bigger proportion of the full-time working week and therefore a bigger proportion of the pay.

The union can also provide education and training. This is where I get to say that I run education and training for trade unions about autism and neurodiversity. Have a word with yours!

Any questions …

[Points from answers to questions]

If your union rep is rubbish, become the union rep yourself!

Unions in industries where people undergo vocational training usually have student membership. So, if you’re a trainee teacher, you can join the National Education Union; if you’re a trainee physiotherapist, you can join the Chartered Society of Physiotherapists. Call up the union for that industry and ask to join, and they’ll probably say ‘Yes, that’ll be one pound a year’ or something like that, because they want to get you in.

The Working Time Regulations specify limits on hours and breaks. You have to have a certain amount of time between shifts and a certain amount of breaks. But this tends to be ignored in workplaces where there isn’t a union organised to make them follow it.

You are under no obligation at all to tell the employer you’re autistic, and they are not allowed to ask except under certain defined circumstances. They can ask you whether you have an impairment that would prevent you doing a core part of the job, but that wouldn’t take the form of ‘Are you autistic?’. They can ask something like ‘Are you all right with working at heights?’ if the job involves working at heights; they can’t say ‘Do you have a diagnosis of vertigo?’.

One of the few times in which they can ask you if you’re autistic is if they need to hire an autistic worker, so positive discrimination is allowed within the law. Say you are 1-2-1 Enfield and you were hiring an autistic peer support worker, then you could ask the applicants whether they’re autistic because you want to hire an autistic worker.

Interviews are a crap way of recruiting people, especially autistic workers, because you get judged on irrelevant personal characteristics. Isn’t the best way of judging whether someone can do a job to get them to do the job?

If you’re an actor and you’re applying for a part in Macbeth at the National Theatre, how would they assess your application? You’d do an audition; you wouldn’t do an exam on vocal intonations in the role of Banquo. If you were a footballer and your life’s ambition was to play for Peterborough United – because why wouldn’t it be? – how would they judge whether to sign you or not? They’d come and watch you play football; they wouldn’t interview you about how you play football.

So, why don’t we apply that process to everything else? Then things like how you come across won’t be relevant, because they’re not relevant in most jobs, are they?

Union recognition. I’m lucky enough to have only ever worked in jobs where unions are recognised, but that’s because I only ever apply for jobs in which unions are recognised! There are laws that make employers recognise unions: you have to have a vote or you have to get 50% plus one of staff in membership. What I would recommend is not necessarily that you unionise it on your own, but you get the union to come and help you do it.

You can become a health and safety rep even if your employer doesn’t recognise a union, because the law says that staff in any workplace are entitled to have a health and safety representative and if there is a union present in the workplace, then the union gets to decide who the staff’s health and safety representative is.

ACAS can help you as an individual autistic worker, but it’s not going to organise to change your workplace. They’re having a neurodiversity conference next spring and I’ll be speaking at that.

Click here for more information about Red in the Spectrum’s training on Neurodiversity in the Workplace, and here for more information about autistic workers and trade unions.