Neurodivergent people’s legal rights at work: Webinar 4

What are your legal rights at work?

On Sunday 4 February, Red in the Spectrum held the fourth in of our series of ten Sunday evening Neurodiversity at Work webinars, on the subject of neurodivergent people’s legal rights at work.

Our seminar presenter, Janine Booth, is not a professional lawyer or legal adviser, but has many years’ trade union experience of legal challenges to discrimination and has researched and written widely on the issue of legal rights at work. Please make sure you take legal advice before starting any legal proceedings.

The webinar explained the following aspects of legal rights at work:

- the Equality Act and protected characteristics

- is a neurodivergent worker disabled?

- types of discrimination

- the Employment Tribunal process

We began by asking participants whether they had taken legal action against an employer. The results were:

- Yes, and I won. 0%

- Yes, and the case was settled in my favour. 21%

- Yes, and I accepted an unsatisfactory settlement. 0%

- Yes, and I lost. 7%

- I’ve considered it, but decided against. 36%

- No, not even considered it. 36%

Legal rights at work: The 2010 Equality Act

This Act consolidated previously anti-discrimination legislation in a new law that addresses discrimination against individuals through the designation of ‘protected charactersitics’. By barring discrimination on the grounds of the protected characteristics, it sets out your legal rights at work in the area of equality and discrimination. Other laws cover other aspects of legal rights at work.

Protected characteristics

It is unlawful to discriminate against a person on the grounds of any of these nine protected characteristics:

- age

- disability

- gender reassignment

- marriage or civil partnership

- pregnancy and maternity

- race

- religion or belief

- sex

- sexual orientation

Discrimination on any other grounds is not covered by the Equality Act, and may not even be unlawful unless it is covered by a different law.

Equality Act: scope

The Equality Act:

- applies to all stages of employment: application, induction, probationary period, promotion, dismissal, redundancy etc.

- applies to all workers regardless of hours of work or contractual status: full-time, part-time, directly-employed, contracted, agency, zero-hours, …

So, you have legal rights at work at every stage of employment and whatever your hours of work or type of contract.

Is a neurodivergent person disabled under UK law?

Click here to read Red in the Spectrum’s article on this question.

- Neurodivergent people are not automatically considered disabled.

- The law says that you are disabled if you have a physical or a mental impairment which has a substantial and long-term adverse impact on your ability to do normal day-to-day activities.

- This is judged on your abilities without any medication or auxillary aids.

- If you submit a claim of disability discrimination, your employer can contest that you are disabled under the terms of the law.

- A formal diagnosis is not decisive.

The government’s guidance on determining whether a person is disabled is here.

Five tests

In practice, you must meet five criteria in order to be considered disabled and have the resulting legal rights at work:

- physical or mental impairment

- In general, neurodivergent people will meet this criterion, by arguing that their neurodivergence is a mental impairment – and in some cases eg. dyspraxia, some cases of Tourette’s, a physical impairment.

- substantial

- In this law, ‘substantial’ means anything more than minor or trivial – it is a broader meaning than in everyday language, where it is usually understood to meet large. Neurodivergent people may have to argue about the extent of the impact to establish that they are disabled.

- long-term

- The legal meaning of this in this context is that the impairment has lasted, or is expected to last, at least twelve months, or the rest of the person’s life if the condition is terminal. In general, neurodivergent people will meet this criterion.

- adverse impact

- A fairly recent case has established that employers may only consider adverse effects, and can not ‘balance’ this by referring to positive characteristics of a worker’s neurodivergence. Therefore, in general, neurodivergent people will meet this criterion.

- ability to do normal day-to-day activities

- The government guidance describes normal day-to-day activities as “things people do on a regular or daily basis” and gives as examples “shopping, reading and writing, having a conversation or using the telephone, watching television, getting washed and dressed, preparing and eating food, carrying out household tasks, walking and travelling by various forms of transport, and taking part in social activities. Normal day-to-day activities can include general work-related activities, and study and education related activities, such as interacting with colleagues, following instructions, using a computer, driving, carrying out interviews, preparing written documents, and keeping to a timetable or a shift pattern.”

- To assert that they are disabled under the law, and therefore to have the associated legal rights at work, a neurodivergent worker will need to explain which of these are impacted in their individual case.

Examples

This is an example of a case where the Tribunal found that a dyslexic worker is disabled and was therefore allowed to pursue a claim alleging breach of his legal rights at work:

Paterson v Metropolitan Police

These are two examples of a Tribunal finding that a dyslexic worker is not disabled:

Herry v Dudley Metroopolitan Borough Council

Iqbal v Mazars LLP

Legal rights at work: Types of discrimination

Direct discrimination

- Treating someone less favourably because of disability.

- The law allows an employer to treat a disabled person more favourably.

- Comparator: someone who is not disabled (in the same way) but whose abilities and circumstances are similar.

- Covers people perceived to be disabled even if they are not.

- Covers people associated with a disabled person.

Examples

- refusing to allow someone to attend a training course because the employer thinks they have Tourette syndrome

- not appointing or promoting someone because they are dyspraxic

- denying flexible working hours to a worker with an autistic child where the flexible hours have been given to another worker without an autistic child.

Indirect discrimination

- When an employer applies a provision, criterion or practice (PCP) which puts disabled people at a disadvantage compared to those who are not disabled in that way.

- ie. Treating everyone the same, but in a way that discriminates in practice.

- An employer can justify indirect discrimination if it is ‘a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim’.

Examples

- Imposing a very strict uniform policy which includes items of clothing that are uncomfortable for neurodivergent workers with tactile sensitivity to the fabric or design.

- Providing all training materials in dyslexia-unfriendly print layout.

- Requiring all employees to work in an environment with noise, visual or other distractions that make it harder for a worker with ADHD to concentrate.

Harassment

- Unwanted conduct which has the purpose or effect of violating a person’s dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment.

- Includes unwanted conduct related to a person’s association with a disabled person.

- Includes spoken and written word, jokes, graffiti, ignoring.

- Tribunal will consider the perception of the target of harassment, and whether it was reasonable for them to find the behaviour offensive.

Examples

- The word ‘Weirdo’ graffiti’d on an autistic worker’s locker.

- Gestures mocking the tics of a worker with Tourette’s.

- Referring to a worker’s child with ADHD as “that psycho kid of yours”.

- Giving a dyspraxic worker a nickname like ‘Klutz’.

Victimisation

- Subjecting a person to a detriment because they have done or may do a protected act eg.

- bringing proceedings under the Equality Act

- making allegations of discrimination

- giving evidence in support of a complaint that someone else has raised

- This means that it is unlawful to discriminate against you for asserting your (or someone else’s) legal rights at work.

- You do not need to be disabled in order to make a complaint of victimisation.

Examples

- Refusing a worker’s requests for overtime after they gave evidence in support of a dyscalculic worker’s discrimination complaint against their manager.

- Sacking a dyslexic worker when they submit a discrimination claim to the Employment Tribunal.

- Not allowing someone to attend a training course because on the last one, they complained about other participants mocking a person with Tourette’s and said that if it happened again, they would complain formally.

Failure to make reasonable adjustments

- When an employer knows or could be reasonably expected to know that a worker is disabled, they must make reasonable adjustments to avoid the disadvantage.

- The duty arises when a PCP, physical feature, or absence of an auxillary aid puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage.

- Whether an adjustment is considered reasonable depends on cost, practicality, effectiveness, disruption, health and safety.

- The employer has to pay for the adjustment.

Examples of reasonable adjustments

- Altering working hours

- Reallocating work duties

- Assistive technology eg.

- speech-to-text software for a dyslexic worker

- talking calculator for a dyscalculic worker

- Providing a mentor for an autistic worker

- Allowing an assistance dog in the workplace

- Allowing a job applicant to give narrative answers rather than multiple-choice

Discrimination arising from disability

- When an employer treats a disabled person unfavourably because of something arising in consequence of the person’s disability.

- As with indirect discrimination, employers can justify their actions if they are a ‘proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.’

Examples

- Sacking an autistic worker for sickness absence for anxiety and depression related to autism.

- Banning a worker with Tourette Syndrome from an event because of their tics.

- Selecting a dyslexic worker for redundancy because of the quality of their emails.

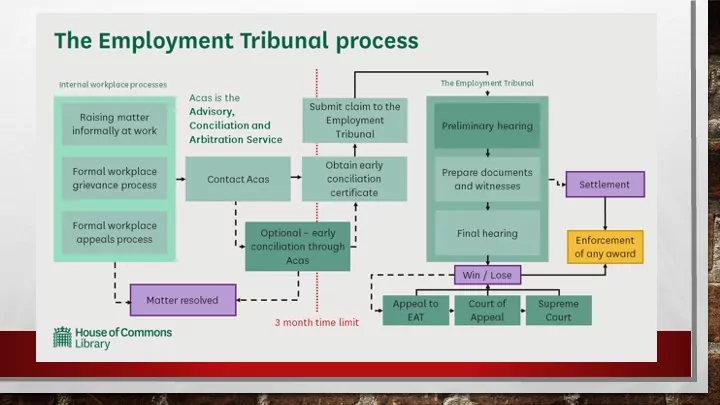

Legal rights at work: The Employment Tribunal process

If you believe that an employer has breached your legal rights at work, you can submit a claim to an Employment Tribunal.

Submitting a claim

- Ask your trade union to support you through the process. The union may or may not provide legal representation for you, but whether it does or not, a union rep can help you with the process.

- Go through your employer’s processes (eg. discipline / grievance) first.

- Submit your claim within three months minus one day of the discrimination you are complaining about.

- Submit an ET1 form, either hard copy or online.

- Provide all the information and evidence that you can.

Early conciliation

- The applicant has to inform the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service of their claim.

- ACAS will try to get the applicant and the respondent (the employer) to resolve the issue via early conciliation.

- If a resolution is not possible, ACAS issues a certificate and the application proceeds.

Talking and hearing

- Both sides prepare and share their evidence, and regularly discuss a possible settlement.

- There may be preliminary hearings ahead of the full hearing to establish specific points.

- The hearing is less formal than a criminal court. Judge and lawyers do not wear wigs and gowns.

- When each side has presented its case and its witnesses, the judge (or panel) will issue a finding.

- You can have reasonable adjustments to the Tribunal process.

Appealing

Either side may appeal the outcome, on a point of law or ‘perversity’.

- First appeal: Employment Appeal Tribunal

- Further appeals need leave to appeal

- Second appeal: Court of Appeal

- Third appeal: Supreme Court

- Outcomes of appeals make case law – they set precedents and establish principles of legal rights at work.

Remedies if you win

- Determination: official confirmation that you were discriminated against, that the employer breached your legal rights at work.

- Recommendations: suggestions to the employer to avoid future discrimination.

- Financial award.

Legal rights at work: Concluding comments

We would all like to think that if something is unfair, then it is unlawful. However, there are plenty of things that are unfair but when are not against the law.

You have some important legal rights at work, and it is very useful to understand them and assert them.

However, the legal process is long and complex, and even if you win, the only thing the Tribunal can make your employer do is give you money.

It is better to take up and resolve issues in the workplace. The most effective way to do this is through organising collectively with your workmates, through a trade union.

Following this webinar on legal rights at work, there are six more webinars in the series, most of which include further aspects of neurodivergent people’s legal rights at work. You may attend whichever ones are most interesting and relevant to you.

Whether you attended this week or not, we hope to see you at some point over the next eight weeks.

Next week, we will be discussing discipline, attendance and performance management. Register here.